THE WORKING METHOD OF A MAGICIAN

06.01.2016

Enkidu Khaled presents his surrealism and his memories at the Frascati Theatre

Working Method, one-actor theater by Enkidu Khaled (Baghdad, 1985) showed at Frascati throughout the first days of December 2015. Arturo Desimone comments.

The Iraqi actor and performer Enkidu Khaled (born 1985) introduced audiences to his magical “working method.” His demonstration of the working methodformed part of his program at the Fras-lab, an initiative of the Amsterdam Frascati theatre to help showcase emerging talents in theatre and dance, by inviting performers each year in order to develop and reveal their work in progress. Frascati is renowned for lending its stage to experimental and provocative pieces, meanwhile hosting almost as many international productions as it does Dutch shows.

The “Fraslab”, as the name indicates, carries the overtone of being an invitation for the audience to tour through a laboratory and Enkidu Khaled proved an alchemist of dazzling and showy experiments in his lab.

Khaled’s project was teamed up with another show scheduled for the same evening, that of the Catalan actress and performer Claudia Amaral, whose group performed the show ”Low-tech”. At the end of the evening, both performers held a Q &A session with the audience and a moderator from the Frascati, defending their project’s findings and intentions. There was ample opportunity to exchange experiences between performer and audience.

As the audience entered the room where Khaled was about to perform, they noticed it was covered with the cloud-like substance of countless drawings. He has accumulated these drawings from past audiences who made them as part of the interactive element of the performance. The drawings are often child-like, drawn by random members of the audience who were asked by Enkidu to picture their unconscious associations with a certain image or event in the personal story told by the actor.

As part of the performance, Enkidu speaks of his experiences as a young artist in Baghdad who was eventually forced to leave his country. Before the intensification of the Iraq war and occupation (and perhaps even during the conflict) theatre always remained an very popular pastime for Iraqis, and for Baghdadis in particular. Yet Enkidu and his friends expressed disdain and contempt for what they considered to be the commercial mainstream of the Iraqi theatre, the generously state-funded and spectacular productions frequented by the average audience. Khaled and his friends sought to devise more politically and socially stimulating aesthetics—but in order to succeed, it became necessary to transcend the usual audience for artistic theatre in Arab countries: an audience typically consisting of other artists and students from art schools. Political art, in order to be effectively political, must of course reach the average audience who would otherwise prefer the spectacular mainstream and commercial productions. He made the audience laugh by telling of a Baghdadi cab driver who said he loved theatre, but was trying to figure out what kind of theatre the young man was involved in “Aha, so you are doing that theatre of those people dressed in black who are horribly depressed about the world and the pointlessness of it all, and are depressing the whole audience!”

“Yes, that is exactly right” the burgeoning actor had answered the cabbie. Honest though self-deprecating, he’d admitted to being one of those excruciating experimental people. But he still wanted to find a way to transcend the tendency of artists to not reach the less open-minded of their audiences, in order to break the insularity of art theatre. It seemed a perhaps impossible task.

One day, during the years of the worsening effects of the American occupation of Iraq, Enkidu -who happens to be named after the monstrous but loyal friend of King Gilgamesh in the ancient Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh- was upstairs in his house, typing out his thoughts for the second scene in his play about Gilgamesh. His typewriter made quite a racket—and lured the worst possible curiosity from outside. “A troop of the people who are now being called the ”ISIS” stood outside my house. My little niece was very afraid to let them in and told them that no one was home.” The death-squad insisted on seeing the man of the house and broke down the door, racing up the stairs to find Khaled with his typewriter. They went on to drag Khaled by his hair (he had an afro’ then) down to the doorway.

I could see and feel the terrible razzia as Enkidu recalled what happened.

Dragging him outside, he was almost executed. He saw decapitated bodies, then in an ecstatic vision suddenly saw himself as a body and separated head, one part still thinking of the other. He became aware of death. In the story, luckily the executioners found a distraction of some form— Ali Baba, from the 1001 Arabian Nights, leaps from the roof in his sash and brandishing his scimitar fended off the executioners, disrupting the violence.

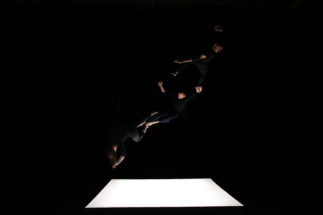

Enkidu confessed that he spent years unable to find a way to tell of his experience. He was unable to do so, until he devised his working method, using dream-like images or symbols. How to do this while being an actor? Simply by transforming himself from the role of actor to that of stage-magician. As a stage-magician, Enkidu powerfully transcends the dilemma and the self-involvement typical of most one-man-shows. Most unlike the austerity of most one-actor (or ‘unipersonal’) shows, his stage uses a very rich alternating and exciting set, consisting of the associative drawings by his audiences.

Enkidu’s ability to combine the experiences of atrocity and war with magical exhilaration is a poetic and necessary artistic response. An artist can do what war journalists and political columnists cannot dream of. Perhaps the actor shares this tendency towards the marvellous in the face of atrocity with another Iraqi artist, the writer Hassan Blasim, whose The Iraqi Christ, his second short-story collection is now available in Jonathan Wright’s English translation from Carcanet publishing.

Blasim’s stories, also partly memoir, alternate between scenes of senseless violence, chaos, blood and faeces found everywhere during war, and the magical in life. In one of Blasim’s stories, an elephant suddenly appears in the ear of a man standing in line for rations. Perhaps Blasim, currently exiled in Finland, has a kindred spirit in the theatre in Enkidu Khaled, now living between Amsterdam and Brussels. Even after the horrors of the occupation and war and the death-squads in Iraq, Khaled insists the Arabian nights are still valid, because without magic there cannot be sanity after the war.

At some point in his narrative in the Working Method test-run, Enkidu interrupts himself. He asks the audience to sit still and relive the most striking scene they had seen that day, a memory or a sight that stayed with them. Enkidu then commandingly invites a volunteer from the audience to make a drawing. I volunteered, and drew the white roses I had seen on a table. Then I drew the associations and memories that other members of the audience called out: a fireman (someone else in the audience tried to correct the person who said fireman, insisting on ‘fire-fighter’), a wedding, a cigarette in a room with closed windows.

Enkidu takes up these memories and uses them as a kind of clay or paint, a raw material for the creation of a visual experience, a speechless performance in which he will continue to tell his personal story to the audience in an enthralling manner. The audience’s memories, like parts of a body after death, do not carry on the identity of any audience member: instead, they are torn to pieces, to be transformed, as broken clay, in the painful performance.

His invitation to one member from the audience to make a drawing, while asking the rest of the audience to provide words they associate with certain words he has chosen in his story, is a gentle and adventurous way to interact with audiences, while at the same time keeping his art-work personal, integral and at the centre-stage. He weaves together a dramatic dream using shreds of our own dreaming and emotive consciousness. The method’s interactivity is luckily only seemingly democratic—somewhere, somehow, Enkidu is feeding the leads, guiding the audience in the phantasy.

Audience participation remains introverted to some degree, as onlookers are allowed to become children again (even if they are not children, but Enkidu also performs at schools.) The method has a surrealist function, bringing to mind the “paranoid critical method” invented by Salvador Dali.

Despite the answers and associations from the audience varying every time, Khaled still finds a way to connect the leads and elements into a story, and uses the unconscious keywords from the audience in order to create an intense performance.

This time around, the process of interrogating the audience led to a story about a firefighter on a burning rooftop. From a trap door, Enkidu pulled a giant wind-making machine that made his red cape ripple as he tore at a bouqet of red carnations, shoving the flowers into his face and eating them. The howling madman resembled the famous portrait by Francis Bacon, grotesquely imitating the gargoyle-like Pope Innocent painted by Velasquez. It was a nightmare ride. It sparkled. There was the inevitable inaccuracy, albeit a slight one: the volunteer from the audience had seen white roses, not red ones. But having such a slight margin of error only proves Khaled’s surrealist method and his alchemy.

Expect, and hope, to see much more from this rising actor and theatre-maker.

Enkidu Khaled studied theatre in the Baghdad fine arts academy and since he came to Europe from Iraq in 2008 has acted in Antwerp theatres. He is currently based in Amsterdam where he enrolled in the masters’ programme of the Amsterdam Theatre School.