Lost and found – the limb you never knew was missing

06.04.2018

What working in a transdisciplinary way means for audience and artists

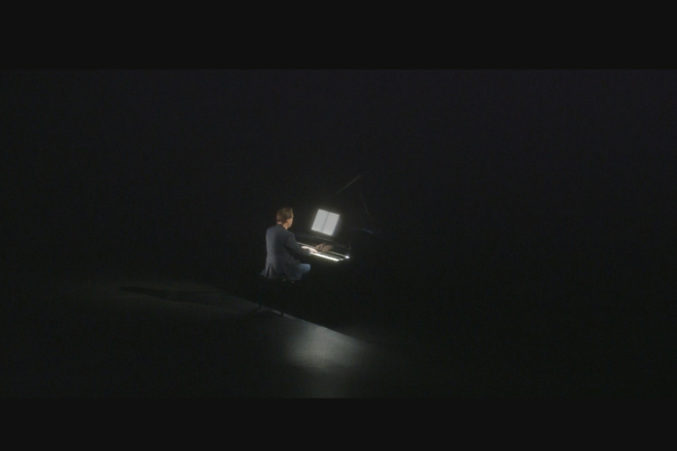

The lights are switched off, one spot lamp is turned on.* In the vague gleam of light, a musician sits behind his piano, waiting to commence. He starts in a soft, slowly and repetitive way. It seems to be a recording studio you are looking at, witnessing a musician record his piece, with only the sound filling the room. The factor of ‘watching’ is nearly eliminated. But the harder the pianist hits the keys and the quicker the notes follow one another, the better you can see him. The beam of light grows stronger and dust from the ceiling swirls all the way down on stage. “A sign of bad cleaning qualities”, you might think, until you realize it is not dust you see. It is snow.

It causes a strange sensation. With the little flakes of frozen rain falling down on the pianist, all of a sudden the view of the scene starts to be important. Sound is reduced to being only one factor in the experience, accompanied by not only seeing a spectacle but also starting to feel cold, as if it were real snow and winter entered the theater space. The music doesn’t appear to be so soothing anymore. And with the snow falling down faster and faster you feel the chaos and the adrenaline. Until that final moment, when you cannot decide whether it is the clouds making the pianist play faster, or the musician controlling the whims of nature. And then … it stops.

An unexpected absence

When you’ve experienced a work of art like “Mars II” – being transdisciplinary in every way the term could be interpreted – you would expect to perceive every element of the experience the artist added for it not only to be ‘just a piece of music’ as alien. But you don’t. In fact you start to wonder what you might have missed in ‘regular’ or disciplinary art – lighting on a painting? Surrounding sounds of a building? – and what surplus value it would have given to the artwork, if you would have noticed before. The artists, featured at the OORtreders festival are all trying to convey an sensory experience in another way than the one would conceive as ‘the normal one’. The spectator takes a look at the world and ‘mis-uses’ his senses; not in the negative way as ‘abusing’ but more as ‘varying from what is seen as normal’. But just as they do this with applying certain disciplines, transdisciplinary artists always find that thin border in between using and misusing – or doing things that aren’t conceived as ‘proper’; seeking conventions and try to break with them.

Take “Tasteful Turntables” for example, where you enjoy a lovely miniature meal in the company of three other spectators. Sound artists Lars and Nikolaj Kynde searched for a way to bring the undervalued aspects of dining to the surface. We all know how food tastes (hopefully delicious), how it looks (hopefully appealing) and how it smells (hopefully great), but it is very hard to describe how food sounds. We know, just by hearing a mixer whip, there is a cake in the making, but this only proves the mixer sounds like that. It says nothing about the sound of the cake or eating it itself. In the company of food artists Mette Martinussen en Augusta Sørensen they searched for a way to make those aspects clear as well, and enrich the act of eating.

As a ceremony, the tiny appetizers are served on a rotating plate on matching tiny china (by Giulia Crispiany) and accompanied by a lamp that switches on as soon as you are supposed to put it in our mouth. At the same time, a sound starts to loom from your headphones. Being a spectator, you expect to miraculously taste different things when listening to the sounds, and of course you don’t. The carrot-creations don’t suddenly taste like pear. But it is striking that the focus is shifting every time the music changes. One taste and you don’t even know what you are eating. A second taste and you feel the textures on your tongue. A third taste and the sweetness of the vegetable reaches your taste buds. It’s not so much the body of the person eating, that reacts in a different way or your tongue that gets numbed or triggered by the music, but it is your own way of focusing that changes with every taste. You start to think about factors that don’t exist, when – while doing so – you realize they do. You’re convinced that this is no exact science and that you dó start to hear your food, or start to hear what changes its taste.

Sensory melting pot

You can hardly explain the feeling (so what am I even trying) but the brothers Kynde did a fine job during their performance. “When working together with the food artists, we soon realized we didn’t speak the same language”, Nikolaj explained to the audience. “Although the four of us speak Danish, the jargon of a sound artist appeared to be incomprehensible for an experimental cook, and vice versa.” To close that gap, they started associating. Stories were told and associated with experiences one would normally never have, but still seemed imaginable. “How would this story taste”, the cook wondered, when at the same time music started to play in the ears of the sound artists.

The results of those associations refer so to be said, to the original story but they also refer to each other. As ‘associations of …’ they work as a sum: if . That, in this case, would mean you can hear tastes, or taste sounds, only by thinking about the same subject and associating; easy math, but with more layers added. It’s no scientific approach; it’s a human approach – approaches and associations that different artists would make in a different way. But you can feel the way something sounds for artist x, and you can taste it the way artist y would extravert it in its cooking. We transgress the boundaries of ‘the possible’ because we use all our senses, the same way the transdisciplinary artists transgress the boundaries of ‘the discipline’ while searching salvation in a combination of many.

Adaptive limbs

Cathy van Eck works in a similar way. In “Hearing Sirens”, she (or a performer) walks through the room with two portable speakers on his/her back. They produce various crackling and crisping sounds. The performer can move them with his or her hands, and when that happens, the sound instantly changes. What the spectator hears are reverberant sounds that hit walls, trees, streets or people and indicate the places the noise can come or where it would bounce up against.

It might recall echolocation, or the way in which (nearly) blind people (or animals) try to imagine the space they’re in. The ticking sound of the stick they are walking with, does not only announce an obstacle that is right in front of them, but also gives them information about how big the space is they’re waking in, or whether or not there are any walls close by. Although Eck is not visually challenged, the ‘playing with speakers’ does seem to be a form of discovering surroundings. She also indicates that, performing the piece in different places and noticing how the sound changes, is part of the work of art.

The speakers in “Hearing Sirens” and the headphones and flickering lamps in “Tasteful Turntables” feel like the limbs you never had, but all of a sudden realize the added value of. Limbs we can teach ourselves to have, for that matter. If it is only time, knowledge and experience that we need to enhance our sense of locality, and it is only calm and adjusted sound we need to taste better, we only need an artist to give us those insights. He provides the playground on which the spectator can experiment.

You wonder whether it is the music that makes you taste better, or the sound that makes you feel the space without seeing, or he visual aspect of snow that makes the piece of music into a stone cold ceremony. But it is not quite that. It’s more as if all those impulses make you feel something else: fantasy and the ability to connect the dots of all the things you feel. The artists are, for that matter, more affection to life itself, than any artist has ever had before. Just as you can catch yourself musing or day-dreaming in real life, you will find a whole new world here, where that is possible as well.

There is no act in real life that is ever monodisciplinary, and that also counts for traditional pieces of art. But it is the focus on the discipline that makes artists as well as spectators lose themselves in things like figuration or tactility, and makes them less eager to think out of the box; think what this might mean for society. Just by trespassing the borders of those disciplines, transdisciplinary artists (and conceptual artists for that matter) create the space to muse about life and think about what art really means.

About terminology

“Transdisciplinarity is a negative term”, speakers at the colloquium said. “It only indicates you cross the borders of discipline. But there should be a positive term, that says what you do use.” This is a very valuable remark, cause the pieces of transdisciplinary art start from an idea and do not limit themselves to a special way of extraversion. As well the Kynde brothers as Cathy van Eck are known as ‘sound artists’, but always challenge themselves to cross those contours of profession. They respectively turn into cooks and architect, while at

the same time they don’t. They stay artists and they keep on working in their own fraction of what the art world is nowadays.

Lars Kynde describes its position as being the following: “I like to call our pieces of art “ceremonies” and I like to call myself a “componist”. I know I make people think I’m some sort of great music composer by that, but I want to show them it doesn’t have to be that way. For me, composing, is making certain actions happen at a certain time.” It’s striking that, when you change the word ‘composer’ by ‘choreographer’, the statement still works. Striking, though not so weird, if you take another look at “Tasteful Turntables”. It was the flickering lamp that told spectators to take another appetizer, and it was also the lamp making spectators move: stretching their arm and bending it again, opening their mouth, closing it again and chewing. The Kynde brothers were composers when it comes to the sensation of taste, choreographers when looking at all the spectators move at the same time.

When being asked if they, themselves, use the term ‘transdisciplinary’, the artists react in a similar way. Lars Kynde says it is some sort of sticker they get put on, which he recognizes from school, but not something he would ever use himself. Van Eck as well says it’s only a term she uses in explaining people what she is doing. “To me, transdisciplinary, means nothing. But sometimes mentioning it, makes it easier for people to understand what I’m working on. For me it is just a vehicle in explaining my way of being, telling people what I’m doing; an organic way of working, of doing what I want to do.”

* What follows is an impression of “Mars II” by Karl van Welden, performed on October 21st 2016 at the OORtreders festival, hosted by Dommelhof, Neerpelt.